Lift High the Cross

This week’s reflection is written by

Mr. Joseph McDaniel, OSFS

Just over a week from now, on September the 14th, the Church will celebrate a most peculiar feast: The Exaltation of the Holy Cross. If the title of this feast doesn’t take each of us aback, it should. Imagine a feast day called “The Exaltation of the Holy Gallows” or “The Exaltation of the Holy Electric Chair.”

If such imaginary titles make us shudder with revulsion, because of their connection in our collective memory with all too real instances of the worst kinds of excess of state power and oppression, then this should give us a sense of how the sight of a cross would have made most people feel during the time of Jesus.

It is no wonder that during the first centuries of Christianity, the Christian community very seldom used images of the cross. i In a time when being a Christian very often entailed risking one’s own life, when martyrdom was a flesh and blood reality that people would often witness with their own eyes, there was no need for the image of a cross to serve as a reminder.

It is somewhat ironic that it was only following the rise of Constantine, and subsequent state support of Christianity, that the cross became a more prevalently used symbol. In fact, Saturday’s feast takes its roots in the said discovery of the True Cross by Constantine’s mother, St. Helena, and Constantine’s construction of the first basilica of the Holy Sepulcher. ii

The frequent alliance of the cross and the sword in the centuries that would follow, throughout the history of medieval “Christendom,” is one that would have likely made the earliest Christian communities scratch their heads to say the least, as well as the gilded representations of the cross that became commonplace in church buildings.

It often takes a prophetic voice to remind us about what being followers of the Holy Cross actually means. Speaking to a congregation in the eastern Roman Empire, St. John Chrysostom reminded, “Do not, therefore, adorn the church and ignore your afflicted brother, for he is the most precious temple of all.” iii In his time, St. Francis de Sales abjured the standards of realpolitik that called for the re-imposition of Catholicism on Protestant Geneva by military offensive. His standard was not a weaponized image of the cross, but instead the standard of the gentle and humble Jesus who actually carried the true cross, who each of us is called to follow in the same way.

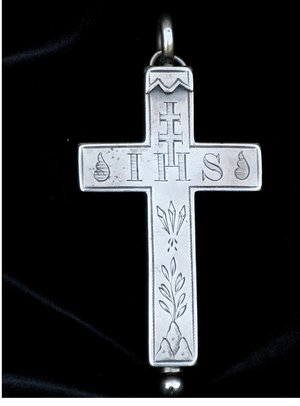

On Francis’ own bishop’s cross, which serves as the model for the profession cross worn by the Visitation sisters, Oblate sisters, and Oblates, there was no corpus, no body of Christ depicted. The body of Christ cannot be reduced to an idealized artistic representation. Each of us, by baptism, is meant to be the gentle and humble body of Christ, serving the body of Christ by living out the Paschal mystery, in which the grace of God emerges victorious over even the greatest evils and sufferings. We can exalt in the cross because we know it points to the Resurrection.

Last month, Jon, Jimmy, and Matt, our newest Oblates, made their first profession of vows. They vowed to “follow Christ more closely in my whole life,” and when they received their profession crosses, they stated, along with St. Paul, “God forbid that I should glory in anything but the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom the world is crucified to me and I to the world” (Galatians 6:14).

What they professed to do, and what each of us professes to do by our baptism, is something that is not only counter-cultural, but indeed would appear to be irrational. We are often taught by society to seek our own comfort and well-being, however that it is defined on any given day. We are wired biologically to seek our own self-preservation and to avoid danger. To follow Christ is to follow him towards the cross, when by most standards we should be doing our very best to walk the opposite direction.

When our instincts tell us to walk away from human suffering, Christ tells us, “go there, follow me,” because behind every cross, there is a person. To “lift high the cross,” as a popular hymn says, is to reach out our hand to lift up the person who is carrying it. When we exalt the Holy Cross, we do not exalt historic planks of wood, nor shiny crosspieces of brass, but instead the sacred humanity of the body of Christ, which is not confined to hang statically in church buildings and museums, but who lives, breathes, and walks among us, on our streets, in our workplaces, in our homes, every day of our lives.

ihttps://www.franciscanmedia.org/exaltation-of-the-holy-cross/

iihttps://www.franciscanmedia.org/exaltation-of-the-holy-cross/; https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/saint/the-exaltation-of-the-holy-cross-594

iii Liturgy of the Hours, Office of Readings, Saturday of the Twenty-First Week in Ordinary Time