In these days of heightened concern and caution regarding the epidemic facing our countries, Visitandines can follow the example of Holy Mother St Jane de Chantal when she dealt with the Plague in 1628-1631.

Bishop Emile Bougaud recounts the story, which we excerpt, a story of generosity, resourcefulness, prayer, penance and deep solicitude for the suffering.

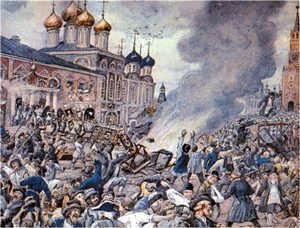

” We can have no adequate idea of what the plague was at the time of which we are speaking. The filth of the cities, the imperfect knowledge of the art of medicine, the absence of regular police capable of maintaining order amid confusion, the contagious character of the disease, believed to be even more contagious than it really was, all contributed to increase the mortality and augment fright and despair. In presence of a sickness which could be communicated by the touch, which was borne on the breath of the victim, with which everything he had used was impregnated, people shut themselves away from sight and contact. They dared see no one, touch nothing. The very food was open to suspicion. The dearest ties were dissolved. At the first appearance of the scourge they fled the cities, which for entire months were turned into deserts. The streets were covered with rank grass and traversed by wolves attracted thither by the scent of the unburied dead. Even the husbandman threw down his spade, and fled from the field. A year of pestilence was succeeded by a year of famine, which, in its turn, brought back the plague, thus forming a deadly and long revolving cycle.

Meanwhile, what became of the convents of the Visitation? Of all the houses in the deserted cities, they alone were occupied. Without food, remedies, medical assistance, without even confessors when the plague had carried them off, the Sisters stood their ground, sometimes spared, sometimes attacked, but always displaying heroic courage and self-devotedness.

Never did Mother de Chantal appear more admirable than under these circumstances. The old ardor of her nature, which for so many years she had been trying to moderate, now reasserted itself. “I have written three or four letters to you, my dear daughter,” she wrote to the Superioress of one of the convents attacked by the plague, “and of what are you thinking not to answer me? Do you not know that I am on thorns?” It was also at this trying period that she displayed that industrious activity, that practical knowledge, that enthusiasm tempered by coolness, so valuable on such occasions. She thought of, she provided for everything. Her heart embraced in its tender solicitude all the wants of her daughters; her mind was as large as her heart. To Lyons, Grenoble, Chambery, and Saint-Flour she sent flour • to Crest, medicines; to Cremieux, clothes and shoes; and to Autun, a flock of sheep. In Paris she called together a council of physicians for the purpose of consulting upon means against the scourge. She assembled a body of theologians, also, to examine whether the Sisters could in conscience leave their enclosure in order to avoid the contagion. She sent circular letters to all her houses to encourage, console, and strengthen the Sisters, and to remind them to prepare for the coming of the Spouse.

By recalling Mother de Chantal to Annecy, to the pure air of the lofty mountains, it was hoped to withdraw her from all danger. But the plague, arrested in its progress by the cold of winter, resumed its course at the melting of the snow, and attacked Belley in February, 1629; Chambery and Rumilly in March and April; and, shortly after Easter, broke out in Annecy.

It was under such circumstances that the community of Annecy chose Mother de Chantal for Superior, May 23, 1629. God so permitted it, that the Order might have the saint at its head at a time in which it was to pass through one of the greatest crises of its history.

The news that the plague had attacked Annecy spread with lightning rapidity through the Visitation houses of France and Savoy, and awakened in them the greatest anxiety. Letters came from all directions conjuring Mother de Chantal to leave Annecy for a place of safety; and, despite the general distress, considerable assistance in money was also sent. The Prince and Princess de Carignan wrote to Mother de Chantal, entreating her to leave the town; and, not being able to persuade her to do so, they declared that they would apply to the Duke of Savoy for an order to that effect. But how could they think that the saint would listen to such a command ?” Oh, pardon my frankness,” she wrote, “but I have not the courage to abandon my flock, for which I should always be ready to sacrifice my life.”

Free to follow her inclination, and resolved not to leave her convent under any circumstances, St. Chantal’s first thought was for her Order. She addressed to all the Superioresses a circular letter containing her last advice in case she fell a victim to the plague. Beholding herself surrounded by death, she said, and exposed to it as much by her great age as by the disease that was destroying nearly the whole city of Annecy, she had maturely considered the means of preserving union and vigor in the Order. She recommended, above all, the exact observance of Rules, without changing anything in them, union and conformity with the convent of Annecy, charity, peace, and fervor. She added the hope that, if these holy principles were maintained, the Institute would continue to spread throughout the world fruits and blessings similar to those it had already produced —” fruits and blessings,” she added, “beyond all that can be imagined, as I myself know.”

This first duty accomplished, Mother de Chantal, finding herself cut off from the other houses of the Order by the sanitary condition of the city, devoted herself entirely to the poor sick dying around her. She sent them flour, money, and remedies, with a generosity equal to their distress. By September she had expended in remedies all the money—and it was a considerable sum—that had been forwarded to her from the other convents in France. In vain did she diminish the portions of the Sisters to increase those of the poor; in vain did she resolve with them to eat only coarse black bread. The end of the month found the supply of grain entirely exhausted. But God, who is bountiful in His mercies, and who never allows Himself to be outdone in generosity, did not abandon His servants. They had robbed themselves for His sake, and He refilled their empty coffers. The old Memoires tell us that ” when Mother de Chantal saw the distress of the poor, she ordered a part of our grain to be distributed among them, so that by the end of September it was all gone, and not a sou to replenish our store. But one of our Bishop’s almoners bought twelve measures of wheat for us, and had them ground; and these twelve measures filled a bin large enough to hold sixteen. God continued to bless this store, so that it lasted until we could procure more,

Prevented by the inviolable laws of enclosure from visiting the sick in person, she induced others to supply her place. Her burning words fired the enthusiasm of the Bishop, Monseigneur Jean-Francois de Sales, who, with a handful of heroic priests, went about ministering consolation to the dying for more than ten months.

She gave out about two dozen Agnus Dei, assuring that they who wore them would not die of the plague. They distributed them among friends, who were constantly with the plague-stricken, and repeated to them Mother de Chantal’s words. Our confidence was fully justified by the result. all preserved from the disease.”

If Mother de Chantal’s influence was so great over those with whom she had only occasional intercourse, what must it have been over the Sisters with whom she lived? It was indeed wonderful, the peace and serenity of her spiritual daughters in the very centre of the infection, and face to face with a death imminent and horrible, that put the bravest to flight. The community exercises were not once interrupted. In the midst of the mournful silence of the city their bell rang out as sweetly and regularly as before, and the same soft and devout chanting was heard behind their grate. “I always saw our Sisters in their usual tranquillity,” wrote St. Chantal; “there never appeared in the community fear, anxiety, or dread. The customary exercises of our state went on exactly without interruption or dispensation, with the usual peace and cheerfulness. . . . Although two or three times there was reason to believe the disease was in the house, yet I never observed the least consternation among our Sisters. They took their little remedies quite cheerfully, each one keeping herself ready to pass into eternity as soon as notified, for we were determined not to expose our good and holy confessor. If any one had stood in need of him, he would have heard her confession from a distance. To administer the Holy Eucharist to her, he would have put the Sacred Host between two small slices of bread and laid it upon the place prepared for the purpose, whence it would have been taken as respectfully as possible by the Sister nurse. This is the way the sacraments are administered in this country to the pest-stricken.”

Such was the peace enjoyed by the community during this period of trial, when neither visits nor letters were received, that St. Chantal used to declare that, if the poor people had not suffered, she would have been glad for it to last; for never before since her entrance into religion had she led so quiet a life. But as the poor were suffering intensely, our saint unremittingly besought God, with tears and sighs, to put an end to the scourge. Besides extraordinary prayers, the Sisters fasted in turn every day on bread and water, performed public penances in the refectory, and disciplined themselves to blood in private. Nearly every day processions were made through the cloister, the Sisters walking barefoot and with a rope around the neck,praying and weeping over the sins of the people, and afterward took a severe discipline for the space of a Miserere

The plague yielded, at last, to these ardent prayers. It abandoned the city after having ravaged it for nearly a year. By degrees it disappeared from Savoy, France, and Italy; and toward the close of 1631 only slight and rare cases of it were met..